Are Global Temperatures Shifting Faster than Animals can Keep Up?

Some animals can move quickly and over long distances. Birds fly from wintering grounds in South America to nest in

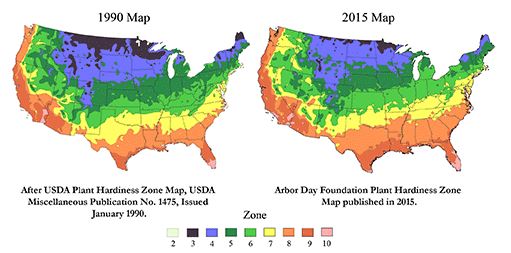

the United States. Tuna, salmon, and sea turtles all move thousands of miles during their lives and return to breed where they were born. But, even highly mobile animals aren’t keeping up with rapid changes in climate, such as earlier arrival of spring and increasingly hotter annual temperatures (see maps). What about animals that don’t have wings or fins, or even legs?! How will they be able to survive in a race to keep up with the climate conditions they are used to?

In just 25 years, global warming has shifted plant hardiness zones northward by a considerable distance, especially in the eastern and central US, where most mussel species occur. (Credit: USDA, Arbor Day Foundation)

A freshwater mussel partially burrowed in a sandy river bottom.

Freshwater mussels have no fins or legs and cannot move very far on their own. They sit snug in river beds filtering particles out of the water for food. As nature’s water filters, each mussel can clean gallons of water each day, and they remove pollutants, sediment, and bacteria, like harmful E. coli. Much of our drinking water comes from lakes and rivers; large healthy mussel populations = human health! But stream temperatures are rising to levels that may be harmful to them. So, we need to understand how mussels will respond to rising temperatures so they can survive and keep our freshwater systems healthy.

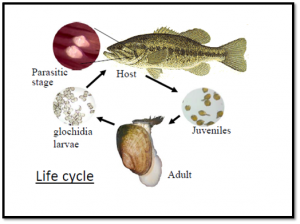

We know that native mussel species use fish to complete their life cycle – larvae attach to a fish and transform into a free living mussel, much like a butterfly transforms from a caterpillar in its cocoon.

Mussels make their biggest moves while attached to fishes.

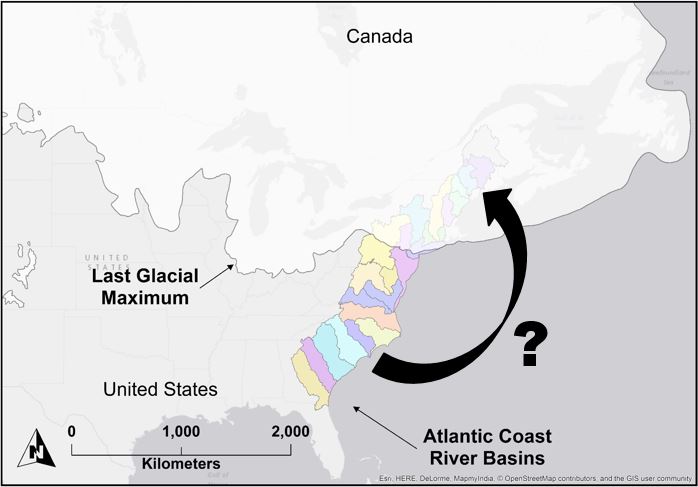

I studied mussel characteristics that might help them move best in response to climate change by looking at species on the Atlantic Coast. Our northern coast was under glaciers 20,000 years ago. But mussels live in these northern rivers now – how did they get there?!

Did some freshwater mussels have advantageous traits that helped them populate northern rivers after the glaciers receded?

I found that mussel species who can hold their larvae over the winter months, and those who can attach to lots of different fish species, as opposed to specializing in just a couple, were most successful in tracking glaciers northward & colonizing new rivers in a warming climate. Full results of this study are available in the journal Diversity and Distributions.

Why do we care about what happens to freshwater mussels in a warming climate? Besides the important fact that they clean our water, they are in trouble. One third of our native mussel species are endangered or threatened already and most others are declining because of human activities, like pollution and habitat alteration (for example, dammed or dredged rivers).

Why else? Mussels are super interesting! Have you wondered yet how those mussel larvae manage to get on a fish? Some mussel moms have tricky fishing lures, like you might find in your tackle box (below left). And some even capture fish to help their babies hitch a ride (below right)! They truly are natural wonders that deserve our attention and respect. We will have to protect them if we want to discover more of their secrets. (Click photos for more!)

You can help protect mussels right now by keeping our waters clean. How?

-

- Follow directions on lawn/crop fertilizers to avoid excess that will wash away.

- Properly dispose of chemicals like motor oil; plant shrubs and trees along your river bank to reduce runoff.

- Join a stream clean up!

You can also help to slow global warming by conserving energy, because a major cause of rampant warming comes from burning coal, oil, and gas – that thickens the heat trapping blanket in our atmosphere. So carpool or bike when you can, turn off lights, reuse/recycle (which takes less energy than mining new materials); or buy local foods that don’t have to travel as far to get to your plate.

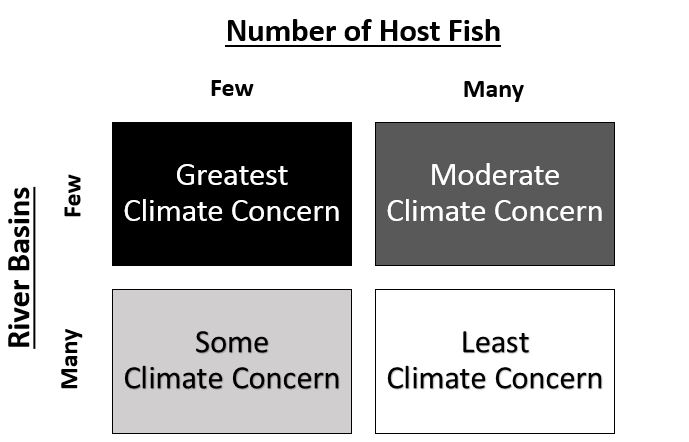

Scientists are working to protect mussels by studying details we lack about many species, like which fishes they rely on. Understanding more about mussels will help us to know which species can keep up with today’s climate warming, and which are most at risk and in need of our attention and help. A climate concern framework based on traits important to climate response may help to classify mussels by climate risk; this concept may be adaptable to other organisms, like some plants, that also rely on other animals (birds or mammals) for dispersal. We can then apply our limited pool of conservation funds more wisely.

Proposed climate concern framework for freshwater mussels, based on number and prevalence of host fishes and current mussel species distribution. Generalist mussels that can use many hosts and occur in many river basins may be classified as “least climate concern”; specialist mussels that can only use a few hosts and also occur in only a few river basins may be of “greatest climate concern”.